The intense struggle to stop the Dakota Access Pipeline, led by Native Americans, highlights the original and continuing “sin” of the United States of America, the genocidal treatment of the indigenous inhabitants of this land and the centuries of betrayal of agreements. But it also offers us a possible pathway for the rectification of many of our present dilemmas, moving us to be guided by the wisdom of indigenous spirituality, respecting and honoring the sacredness and intelligence of the natural world.

The intense struggle to stop the Dakota Access Pipeline, led by Native Americans, highlights the original and continuing “sin” of the United States of America, the genocidal treatment of the indigenous inhabitants of this land and the centuries of betrayal of agreements. But it also offers us a possible pathway for the rectification of many of our present dilemmas, moving us to be guided by the wisdom of indigenous spirituality, respecting and honoring the sacredness and intelligence of the natural world.

The encampments at Standing Rock alongside the Cannonball River that feeds the Missouri have brought together a multi-cultural movement that recognizes the leadership of Native American tribal elders and activists from over 300 Indian Nations. They have come together in a non-violent and spiritually centered movement for protecting the water and land. They have specifically defined their actions as protective rather than as protest. From their spiritual perspective, the true function of the Warrior is to protect, whether in reference to the body, the community, the nation, or the planet.

Stepping back from the particulars of this struggle to protect the land and water sacred to the Lakota Sioux and stop the continued expansion of fossil fuel infrastructure, it is important to recognize the significant inclusion of the indigenous spiritual attitude with social justice and environmental activism. This wider and deeper view of the human relationship with Spirit and Nature, e.g., calling attention to the sacred fire, sacred water, sacred sky, sacred Mother Earth, not just in words, but in the way we feel and the way we move about, is transformative and infectious. It holds keys to the healing power needed to shift humanity from the destructive trajectory we seem locked into.

How we as individuals and as groups of social justice and environmental activists learn from these ancient ways that are connected to Mother Earth herself, needs to be made very conscious. It will not be helpful (in fact it is disrespectful) to mimic the practices of Native Americans. But we can learn to re-awaken what is indigenous (innate) in all humans, the mutual and respectful sense of holiness in Creation and Creator, whether we currently experience them as distinct or as One. This sensibility has been covered over by a radical over-emphasis on the rational, logical, thinking-mind devoted to technological control of our environment and ourselves. What is being called forth is a heart-centered and holistic way of being and relating, one of communion-with rather than control-over.

Through the centuries of subjugation, native peoples have passed along the practices, stories and songs that sustain this consciousness in each region and on each continent. We immigrants have the opportunity to listen to them and hear the resonant tones of our own indigenous ancestors calling from within, finding our own pathways towards a balance of the elements of the web of life. Along the way, it’s important that we not confuse embracing “indigenous spirituality” with exploiting or coopting the objects, rituals and ceremonies of specific tribes or peoples. Native Americans are understandably very sensitive to this abuse. In “Native American wannabes: Beware the Weasel Spirit,” Lou Bendrick points out that, “Members of the Lakota tribe have declared war on exploiters of their ancient spirituality. Their declaration states that they have ‘suffered the unspeakable indignity of having our most precious Lakota ceremonies and spiritual practices desecrated, mocked and abused by non-Indian ‘wannabes,’ hucksters, cultists, commercial profiteers and self-styled ‘New Age’ retail stores and … pseudo religious corporations have been formed to charge people money for admission into phony ‘sweatlodges’ and ‘vision quest’ programs …’”

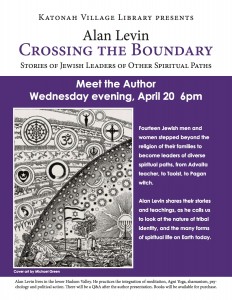

On the other hand, I personally know a number of White, Black and Latino women and men who have submitted themselves to decades of rigorous, disciplined education under the guidance of Native American elders and have been sanctioned to practice and teach certain aspects of those traditions. In my interview with Tom Pinkson, (see Crossing the Boundary – Stories of Jewish Leaders of Other Spiritual Paths), he describes his initial passing through the buckskin curtain when he began studying and being tested by a Native American teacher which led up to his decade-long apprenticeship with Huichol shamans in Mexico. Ken Cohen, also interviewed in Crossing the Boundary, studied intensively for many years with his teachers, Keetoowah, Rolling Thunder and Grandmother Twylah Nitsch, and was initiated and adopted by a tribal clan. These two, and quite a few other White (in this case, Jewish) men and women, respectfully entered into a relationship with indigenous spiritual teachers and tribes and only practice and teach what they have been given permission to share.

Though few will feel called to cross that boundary so deeply, by embracing an indigenous spiritual outlook the environmental and social justice movement is shifting the very mindset in which it has viewed the problems and solutions it addresses. We are finding ourselves gazing up at the sky, sitting by the sacred fire, getting down on our knees and kissing Mother Earth as we face those of our brothers and sisters who have forgotten what they have lost, forgotten what they’ve forgotten.

For more information see the Standing Rock Sioux Nation website: http://standwithstandingrock.net/

A personal observer’s account of the activity at the encampments: Mark Johnson’s, “Standing Rock #NoDAPL. It’s not so complicated, But it is complex.” http://clbsj.org/news/2016/11/23/standing-rock/

A deep mythological/archetypal/political view, “History in the Making at Standing Rock.” By Paul Levy: http://www.awakeninthedream.com/standing-rock/

A look at the growth of the indigenous spiritual focus in the environmental movement: “The growing indigenous spiritual movement that could save the planet.”https://thinkprogress.org/indigenous-spiritual-movement-8f873348a2f5#.u1q1rzood