In the modern secular world, it takes courage to cross the boundary from watching the events of the world, to becoming an activist in bringing about change and transformation of the direction of society. Likewise, even for those immersed in a religious tradition, there is a boundary to becoming a truly spiritual being. The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. crossed both of those boundaries and changed our world. I was honored to be asked to write a piece about him for the Fellowship of Reconciliation which I’ve linked to here.

Rev. Martin Luther King – Spiritual Activist

–Alan Levin

“Hate cannot drive out hate: Only love can do that.” – Martin Luther King, Jr.

“Hate never yet dispelled hate. Only love dispels hate.” – Buddha (from the Dhammapada)

With an iconic figure such as the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., whose brief life shook this nation forever, people pick and choose what they want to see of his multi-faceted legacy.

Currently we have the literal whitewashing of his very radical message as politicians who want to discredit affirmative action and impose voter I.D. laws use quotes from Martin Luther King to justify their supposed “color-blind” objectives.

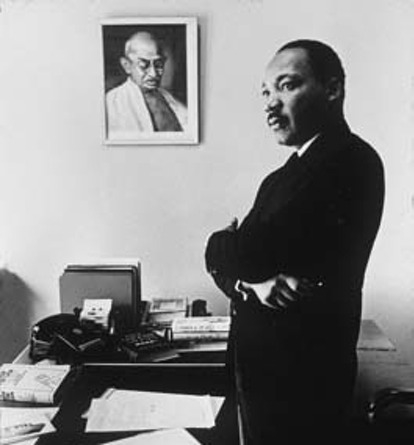

On the other hand, activists of the Left often overlook the fact that Reverend King was a truly religious, spiritual man. He was a Christian. But more so, he was a holy man in the prophetic tradition that transcends any one religion.

I have no knowledge of King’s inner life, but from what I do know of his life and statements, he regularly sought counsel from the divine within for guidance and tried to walk and talk in alignment with that.

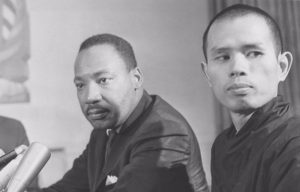

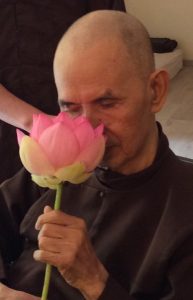

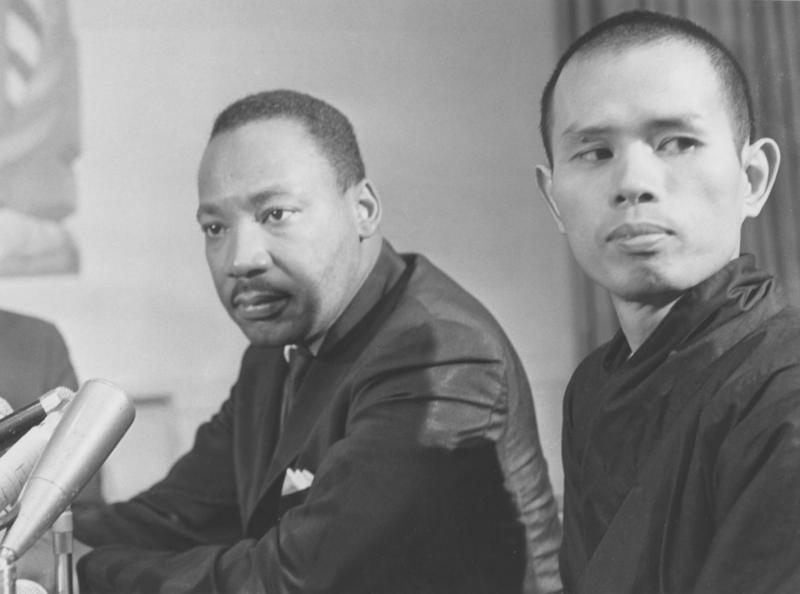

I do not know if he ever studied formal meditation from Eastern teachers, but he found deep friendship, mutual respect and admiration with Vietnamese Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh. It was after his talks with Nhat Hanh that Dr. King came out publicly against the Vietnam War. In 1967 Dr. King nominated Nhat Hanh for the Nobel Peace Prize.

In any case, King found from his inner sojourns, his reflections and prayers, his own unique understanding and expression of many of the deepest teachings of spirituality, East and West.

Everything is interconnected. Everything affects

everything else. Everything that is,

is because other things are.

–Basic Buddhist teaching of Dependent Origination

“All I’m saying is simply this: that all mankind is tied together; all life is interrelated, and we are all caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly. For some strange reason I can never be what I ought to be until you are what you ought to be. And you can never be what you ought to be until I am what I ought to be – this is the interrelated structure of reality … And by believing this, by living out this fact, we will be able to remain awake through a great revolution.”

–Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr.

(Commencement Address at Oberlin College, 1965)

His call to, “remain awake” as a primary goal testifies to the importance King placed on consciousness, not just our behavior as humans, as activists. He wanted us to be awake not just to the suffering, or even the systemic causes of suffering, but awake to the nature of reality. In this, he is in alignment with His Holiness the Dalai Lama: “What the world needs is a spiritual revolution.”

I believe Dr. King understood from his own experience the need to take time to cultivate that spiritual consciousness, to cultivate a heart filled with compassion and love in the face of injustice, hatred, and violence. This cultivation is the very heart of meditation.

King’s good friend Thomas Merton, the Roman Catholic monk, deeply involved himself in Eastern philosophy and spirituality. He counseled us to “withdraw into the healing silence of the wilderness … not in order to preach to others but to heal in (ourselves) the wounds of the entire world.” And yet, King did preach once he felt his voice was a channel for that greater whole.

Somehow, through his inner searching and his confrontation with the realities of the world, King realized for himself that freedom from the fear of death is the promised land of spiritual work, the realization of the greater awareness that lies beyond the phenomenal world. What else could he have experienced that brought him to say:

“Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will. And He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over. And I’ve seen the Promised Land.”

As I was writing this, a good friend, Sister Dorothy Maxwell, sent me a profound article, “The Ecology of Prayer” by Fred Bahnson in Orion Magazine. In it, Bahnson quotes the seventh century Saint Isaac of Syria, “An elder was once asked, ‘What is a compassionate heart?’ He replied: ‘It is a heart on fire for the whole of creation, for humanity, for the birds, for the animals, for demons and for all that exists.’”

Surely, the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., was actively engaged in transforming his heart towards that fuller compassion through his meditations, his prayers, and his activism. Surely, it is our task to carry on that work.

Alan Levin is cofounder of Sacred River Healing. A member of the Fellowship of Reconciliation, Alan is involved in a range of initiatives in New York’s lower Hudson Valley that engage the intersections of racial justice, peacemaking, ecological sustainability, mind-body healing, and spiritual awakening.

Photos: (1) Rev. King with Thich Nhat Hanh in June 1966, courtesy of FOR Archives & Plum Village Monastery; (2) Photo by Bob Fitch, used with permission, FOR Archives.